|

When my son was young, he left a plastic Pepsi bottle with a message in it on the windowsill of my studio. The note —written in the childish calligraphy proper to his age— was a plea for medicine and food for the Cuban people. That simple object, which to me seemed so beautiful and full of meaning, immediately became the point of departure for one of my works.

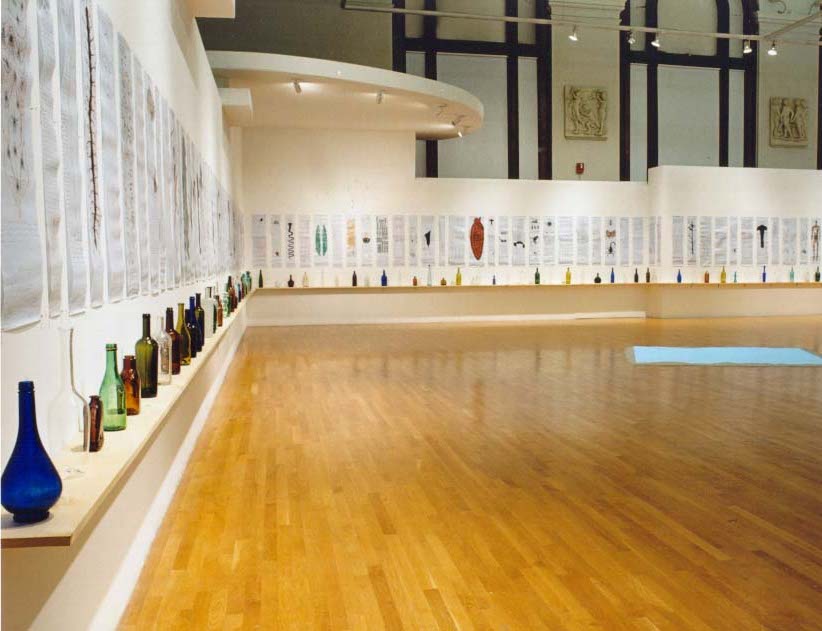

In the complex process of creation, it often happens that a simple element becomes the detonator for a series of complex ideas that later coalesce into a definite image. It was then that I began to elaborate Bottles to the Sea. At that time, I was working on a group of paintings about the relation of the individual to the place in which he lives; how it is that one creates and modifies the other in an extremely complicated and dynamic process of mutual interaction. Each of the paintings alluded to a specific place. Bottles to the Sea arose as homage to the Malecón. This is a wide avenue with a wall on the seaward side where people go to sit and contemplate the horizon. For me, this confrontation has a strong symbolic connotation in that Cuba, in addition to being an island, is politically isolated, and the majority of Cubans have no possibility of leaving the island or ever knowing what the world is really like. On the other hand, and paradoxically, only 90 miles from the Cuban coasts are the Florida Keys and a little further north the city of Miami, where a great number of Cubans live. When I lived in Cuba, each time I passed by the MalecónI thought of my mother who lived on the other side of the sea and of other Cubans, who just like me, suffered because their families were divided by political circumstances. Havana’s seawall constitutes a barrier; it is the limit that restricts the reach of an island and its inhabitants. To throw a bottle into the sea with a personal message means to go beyond those limits, to escape in some form, if only symbolically. Later, as I developed the idea, I realized that the work could escape its context and its original circumstances and become something more universal. To throw a bottle into the sea meant, then, to escape the spiritual limits of the human being. In 2001, the Malecón celebrated the one hundredth anniversary of its construction. It seemed to me a perfect opportunity to convert the piece in homage of its centenary. Thus, I completed one hundred drawings, which, in the form of illuminated manuscripts, consisted of a compilation of texts and images taken from the notebooks that have accompanied me throughout my career. Thus, the piece became a compendium of my personal experiences, of my ideas and drawings of every kind, which were mixed with the history of the city where I was born, educated, and grew up. The installation unfolded in space is also an allusion to the wall and the sea. The piece consists of a long shelf that supports a sequence of one hundred bottles. The bottles, all of different sizes and colors, contain the messages that later are thrown to the sea. Every bottle on the shelf also contains its respective drawing, all of which were done on light blue paper as an allusion to the sea. Each drawing possesses a number corresponding to the order of its realization, but that does not necessarily correspond to its order in the installation. The work has a ludic character and is always mounted differently, adapting itself to the space. The messages are conceived to be cast into the sea. The work’s method is chance. It attempts to simulate existence itself, in the way human events happen following the incalculable course of what we call destiny. Each time I go to a place near the sea, in any point around the world, my son chooses one among many pieces of folded paper kept in a small box. Each paper has a number between one and one hundred, which of course corresponds to the numbers of the messages. It is here where the play of chance and meanings begins. Each drawing has a title whose election will begin a relation with the destined place. Once thrown to the sea, the possibility of the encounter of this message with an unexpected receiver begins, at an indefinite time and in an unforeseen place. In turn, the person who finds the message becomes an active element in the work, forming an indispensable part of its play of meanings. With the drawing-message, I have included a note. The first line reads: “This drawing is yours.” After this, I explain briefly the project and the importance of having a response from its bearer. Fundamentally, the expected commentary is where and when the message was found and if this has some meaning for or connection to the person. Like the book I-Ching, the messages are symbols with their meanings that are found by chance and from there a bridge is created. In addition to the bottles and drawings, the installation includes a map on which are signaled the launching points and their trajectories in the case of a message being found. Also, the work includes a photographic and video documentation of all the launchings. Over time, this documentation will be the complete and unique testimony of the installation. The launchings are substituting themselves with the documentation, thus the installation is changing; each time it is shown it is different, until the point that, when all the drawings have been thrown to the sea, only the visual documentation of photographs and video will remain. The work was exhibited for the first time at the 7th Biennial of Havana, together with the first launch on the Havana seawall in the year 2001. Since then, the piece has been shown in the United States, Mexico, and Switzerland. As of the end of 2019, there have been twenty-three launchings: Cuba, the United States (on the Pacific and Atlantic coasts), France, Mexico, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland (the Rhine), Italy, Turkey, Greece, Ireland, Morocco, and Brazil. Four messages have been found. One of them was launched in the port of Barcelona, Spain, and it was found by a German tourist on the beach in Alcudia, Mallorca. The other three were launched and found in Turkey, Ireland, and Greece. |

|